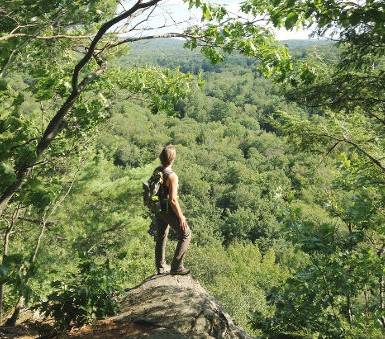

How does nature affect our well-being? Learn the background and some great suggestions from volunteer Julia Wolst.

Twenty years ago, as a post-secondary student, I was drawn to the greenhouses at the university every weekend. No, I wasn’t particularly interested in studying the botanical names of what was growing within. What I needed was the sense of rest and rejuvenation I found in that small, glass-enclosed space.

At particularly stressful times in the school year, I could spend an entire afternoon among the plants, escaping the crowded hallways, crammed library and busy city streets. Among the greenery, I found my own silent stress therapy.

The psychological benefits of time spent in nature have been documented in various studies. Time and again, research and anecdotal evidence suggest increased exposure to outdoor activity promotes positive mental health in children and adults. Regular connection to outdoor environments enables us to deal with conflict more easily, to perform better at school and work, to sleep more restfully and reduces overall stress levels in people of all ages.

Results of recent studies are also suggesting engagement in nature measurably reduces off-task and disruptive behaviour for children with deficits in attention.

University of Michigan professors Rachel and Stephen Kaplan were among the first to study the restorative power of nature. Their research concludes most mental distress and behaviour problems are the result of mental overload and fatigue. Our brains tire from attempting to concentrate on one thing at a time in the face of a multitude of competing distractions.

“Sustained directed attention is difficult and fatiguing. When people talk about mental fatigue, what is actually fatigued is not their mind as a whole, but their capacity to direct attention.”

We try to focus on the report or math problem at hand while blocking out nearby conversations, other people moving around us, the television, the traffic, the dust bunnies under the table begging to be cleaned up. Telephones ring, email pings, text messages bing; sounds, smells, lights and colours. How many things are you aware of competing for your attention as you read this?

Stephen Kaplan theorizes: “Sustained directed attention is difficult and fatiguing. When people talk about mental fatigue, what is actually fatigued is not their mind as a whole, but their capacity to direct attention.” Quite simply, our minds are exhausted from overstimulation.

Many popular, non-work leisure-time activities are also mentally distracting — loud, bright and demanding of attention (sporting events, television, video games, parties). Or, they require focus and concentration (woodworking, handcrafts). They distract from work or school stress, but they don’t allow the brain “downtime” to rest.

What is it about time in nature that is so restorative?

By comparison, time spent in nature is gentle and soothing to the brain. Calm, quiet, muted colours, slow, flowing movements — immersion in nature allows the mind to wander and recuperate. Despite what video-game-addicted middle-grade students may claim, a “boring” walk in the woods is beneficial to their brains and will help them to do well in school.

The sensory under-stimulation of walking in the woods, paddling a canoe or working in the garden rests the active attention portion of our brain. Programs like the Warrior Hike — Walk off the War recognize this and successfully use long-distance hikes in nature to allow soldiers to mentally decompress and quiet their minds after the trauma of combat duty.

Many of us haven’t thought about how to add the experience of nature into our hectic lives on a daily basis. But little tweaks can make a big difference in how often we experience the natural world.

- Schedule daily morning walks or make an after-dinner walk around the block part of your evening routine.

- Take a detour on your way home to walk down a local tree-lined path or trail rather than taking a shortcut across the parking lot.

- Watch birds at a feeder or nurture windowsill plants (for those housebound).

- Alter long-distance driving routes to allow for a few minutes to get out and stretch at parks or alongside water.

- Plan to exercise outdoors as much as possible. Stretch or do yoga in the back yard rather than in the loud, bright chaos of the gym. Run the dirt trails rather than pounding the pavement.

- Take your morning coffee or evening tea outside — sit on the front steps or balcony. Be sure to bundle up and put a folded blanket or cushion under your bum in cold weather. There is nothing quite like mittened hands around a steaming mug.

- In winter or inclement weather, find indoor spaces with an element of green space. Botanical gardens, city greenhouses or even wandering through the greenhouse of a local nursery or garden centre can offer eco-therapy benefits.

Good health requires more than good food and exercise. Our brains need care, too. Thankfully, taking some regular outdoor eco-therapy is much more pleasant than any diet or new exercise plan. It is easy to forget how amazing we feel after time outdoors, but the more often we get out, the easier it is to remember. Make time in nature a priority in your life. Rewards are out there. You should go.

Written by Julia Wolst.