With the return of the monarch butterfly, begins the start of the monarch monitoring season for the Couchiching Conservancy community science program. Monarchs are Endangered in Canada1 , and face various threats across their range including habitat loss, pollution (herbicides and insecticides), extreme weather, and disease 2. Our monarch monitoring program gathers information on monarchs and milkweed patches at local nature reserves. To contribute to research on a larger scale, we share our data with other organizations such as Mission Monarch and the Natural Heritage Information Centre.

To collect the data, trained volunteers survey their assigned milkweed patches monthly from June to August. They inspect milkweed plants and tally the number of monarch eggs, caterpillars, chrysalises, and butterflies. This provides evidence of monarch breeding, and gives a snapshot of monarch populations in the patch overtime.

Monarch caterpillars undergo five distinct stages of growth known as instars, with each stage characterized by specific size and appearance. When volunteers encounter a caterpillar, they use a specialized ruler to help them determine the instar. This June, monarch monitors surveyed 4 different milkweed patches at nature reserves protected by the Couchiching Conservancy. A total of 11 eggs, 1 caterpillar and 2 adult monarch butterflies were reported.

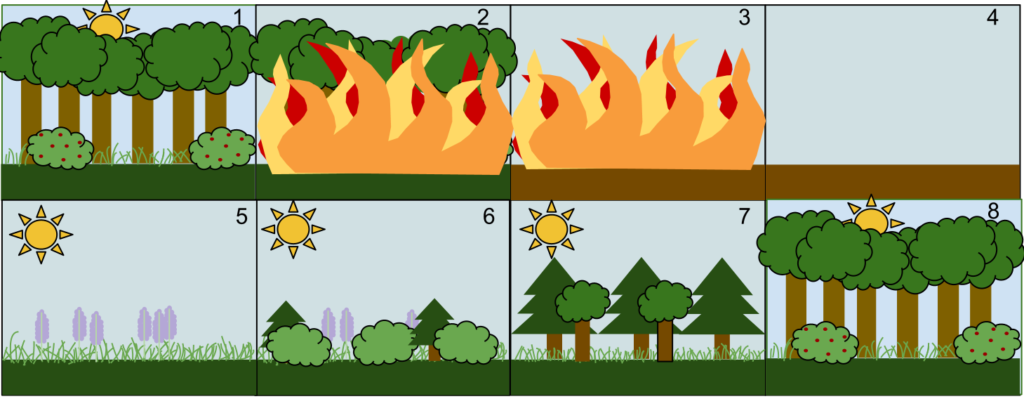

Volunteers also photograph their milkweed patches and record details such as milkweed density and patch size. This documents the ecological succession of the habitat overtime. Ecological succession describes the natural transition of landscapes following disturbances like forest fires or human activities, as they gradually transform from barren environments into meadows and, eventually, forests. Milkweed is an early succession plant and thrives in habitats such as meadows and roadsides.

Our monarch monitors tend to observe fewer monarchs in milkweed patches at later succession stages, potentially due to increased predator presence3. Volunteers have also documented other wildlife in these meadow habitats, including garter snakes, assassin bugs, and indigo buntings, demonstrating the rich biodiversity of these habitats.

Our monarch program is unique because our summer staff coordinate it each year, providing a leadership opportunity for young conservation professionals. Special thanks goes out to our dedicated monarch monitoring volunteers for their continued contribution to the study of these insects.

Ways that you can celebrate pollinators this summer:

Monitor for monarchs in your own yard with Mission Monarch

Learn about pollinators with our pollinator bingo activity sheet. It’s fun for the whole family!

double-sided printout (2 copies per page – requires scissors to separate)

References:

Government of Canada. “Monarch (Danaus plexippus)”. Species at Risk Public Registry, 12 December, 2023 https://species-registry.canada.ca/index-en.html#/species/294-90. Accessed 7 June, 2024.

COSEWIC (2016). “COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Monarch Danaus Plexippus in Canada”. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. pp xiii + 59 pp. Species at Risk Public Registry Website. Accessed 7 June, 2024.

Haan, Nathan L., and Douglas A. Landis. “Grassland Disturbance Increases Monarch Butterfly Oviposition and Decreases Arthropod Predator Abundance.” Biological Conservation, vol. 233, May 2019, pp. 185–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.007. Accessed 6 June, 2024.

Article by Aiesha Aggarwal, Conservation Analyst with The Couchiching Conservancy